BLOGPOST

Futures research (including Foresight and Horizon Scanning) has emerged as a key instrument for the development and implementation of research and innovation policy. The main focus of activity has been at the national level. Governments have sought to set priorities, to build networks between science and industry and, in some cases, to change their research system and administrative culture. Foresight has been used as a set of technical tools, or as a way to encourage more structured debate with wider participation leading to the shared understanding of long-term issues. There are many definitions of Foresight and Horizon Scanning in the futures literature, so in this blog I would like to share my own (2011) definitions:

Foresight is a systematic, participatory, prospective and policy-oriented process which, with the support of environmental and horizon scanning approaches, is aimed to actively engage key stakeholders into a wide range of activities “anticipating, recommending and transforming” (ART) “technological, economic, environmental, political, social and ethical” (TEEPSE) futures.

Horizon Scanning (HS) is a structured and continuous activity aimed to “monitor, analyse and position” (MAP) “frontier issues” that are relevant for policy, research and strategic agendas. The types of issues mapped by HS include new/emerging: trends, policies, practices, stakeholders, services, products, technologies, behaviours, attitudes, “surprises” (Wild Cards) and “seeds of change” (Weak Signals).

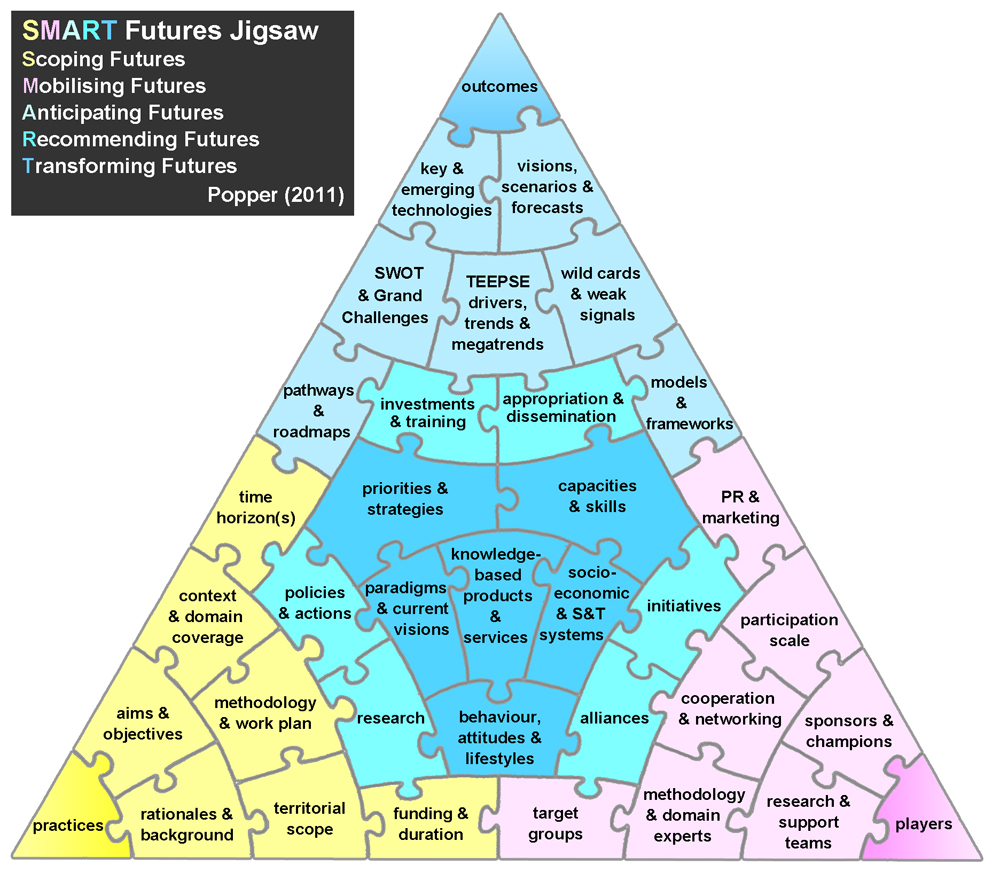

To better understand the core elements of Foresight and Horizon Scanning (FHS) activities, I developed a practical framework which I called the S.M.A.R.T. Futures Jigsaw. It contains 36 elements, which relate to the five phases of FHS processes: Scoping, Mobilising, Anticipating, Recommending and Transforming. Each of these phases and elements will be explained in greater detail below. NB: In an academic context I would normally argue that the main difference between Foresight and Horizon Scanning is that the latter does not necessarily involve "recommending" or "transforming" futures. However, in practice, the boundaries between Foresight and Horizon Scanning are becoming rather fuzzy, with several HS activities resembling what we (in Manchester) would normally call Foresight.

In the SMART Futures Jigsaw, seven elements help to map practices and relate to the Scoping futures phase of a Foresight or Horizon Scanning process:

- - Aims and objectives – To define general goals and specific objectives of a study.

- - Rationales and background – To justify and clarify the needs for the Foresight activity and its boundaries.

- - Context and domain coverage – To define key RTD settings and areas/sectors.

- - Methodology and work plan – To define the RTD process and related methods.

- - Territorial scope – To define the sub-national, national and supra-national coverage.

- - Funding and duration – To define the cost and duration of key activities.

- - Time horizon(s) – To establish how far into the future should we look.

Another seven elements help to map players and relate to the Mobilising futures phase of the Foresight activity:

- - Sponsors and champions – To define financial and/or political supporters.

- - RTD and support teams – To identify team leaders, managers and supporting staff.

- - Target groups – To identify potential users of results.

- - Participation scale – To measure the levels of interaction and openness of a study.

- - Public relations (PR) and marketing – To increase the visibility and reach of a study.

- - Networks and (international) cooperation – To promote cross-fertilisation/collaborations.

- - Methodology and domain experts – To improve the design and quality of RTD activities.

Overall, nineteen elements can be used to map outcomes. Of these, seven features can be considered formal outputs of Foresight and Horizon Scanning (FHS) processes, six are conventional research outcomes and another six features are ultimate the Foresight activity outcomes resulting from the various dynamics and synergies activated in the SMART phases of a fully-fledged FHS process. The following seven formal FHS outputs are distinct features of the Anticipating futures phase, which access and distil collective intelligence to think more systematically about the future in exploratory and/or normative ways.

- - Visions, scenarios and forecasts – To identify possible (desirable/undesirable) futures.

- - Critical and key technologies – To identify important technology needs.

- - SWOT and Grand Challenges – To identify major areas of concern and key assets.

- - TEEPSE drivers, trends and megatrends – To identify major forces of change.

- - Pathways and roadmaps – To define future directions and how to get there.

- - Models and frameworks – To define new conceptual and action tools.

- - Wild cards and weak signals – To identify potential "surprises" and "seeds of change".

Note: TEEPSE stands for Technological, Economic, Environmental, Political, Social and Ethical.

There are six conventional research and technology development (RTD) outcomes that are linked to the Recommending futures phase. Some of these can be found in standalone policy briefs, academic/professional journal articles produced by members of the Foresight activity team and executive summaries of reports and publications prepared by the Foresight activity practitioners, organisers and users. Other outcomes can be mapped with the help of stakeholder interviews/surveys and documentary analysis. They are:

- - New policy and actions – To provide possible courses of action.

- - New/further research and the Foresight activity – To address new research questions.

- - New/further investments – To efficiently distribute our limited RTD resources.

- - New appropriation and dissemination – To share knowledge and insights on relevant issues.

- - New alliances – To combine efforts on common/shared visions and objectives.

- - New initiatives – To bridge gaps and strengthen key actors.

Finally, there are six ultimate outcomes related to the Transforming futures phase of the Foresight activity processes.

- - Renewed priorities and strategies – To define concrete action plans and targets.

- - Renewed capacities and skills – To increase absorptive capacity.

- - Renewed paradigms and current visions – To understand and accept future changes.

- - Renewed socio-economic and S&T systems – To address opportunities and challenges.

- - Renewed knowledge-base products and services – To achieve higher development levels.

- - Renewed behaviour, attitudes and lifestyles – To cope with new/changing systems.

The first phase of Foresight & Horizon Scanning (FHS) processes is about scoping futures. This involves the definition of the aims and objectives of the study, which are often related to a broader set of rationales (e.g. orienting policy and strategy development) and background conditions (e.g. events, documents, etc.). This is followed by the description of the context (e.g. EC funded foresight activities) and the domain coverage (e.g. energy, nanotechnology, security, etc.). Then the methodology is defined (by selecting and combining methods) and a clear work plan is prepared (by defining major activities, tasks and milestones). Next come the decisions about the territorial scope (considering the implications of choosing one or more of the following options: supra-national, national and sub-national) and the time horizon(s), in order to decide how far should we look into the future. Sometimes the funding and the duration of Foresight are independently determined by the context (such as open calls for tenders, for example). However, even if the total funding and duration in months are pre-defined, it is important to make sure that the overall scope of the project is realistic considering available resources. The key elements of the scoping futures phase are used in the mapping of FHS practices.

For practical reasons mobilising futures is represented as the second phase of FHS processes. However, some activities are simultaneously initiated with the scoping phase, such as contract negotiations with the sponsor or definition of the research and technology development (RTD) teams; while others run throughout the life of the project (e.g. engagement of target groups). This phase requires regular (sometimes face-to-face) meetings and discussions with sponsors (responsible for both economic and political support) and champions (influential individuals capable of mobilising key stakeholders). The clear definition of capacities needed to conduct the study is one of the most critical success factors. By capacities we mean the RTD team (i.e. project leader, researchers and technology developers), support team (responsible for travel, logistical and administrative issues), methodology experts (providing guidance during the whole process) and domain experts (e.g. thematic specialists). Depending on the nature of the study (and of the sponsors!), the Foresight team may need cooperation and networking to increase the participation scale and specific target groups (e.g. government organisations). Finally, one element that is often neglected or underestimated is the need for coherent public relations (PR) and marketing strategies. While the former helps to mobilise decision-makers, the latter is essential to communicate and disseminate key activities and findings. The main elements of the mobilising futures phase are used in the mapping of FHS players.

The third phase of the FHS processes is about anticipating futures, i.e. producing the “formal outputs” of Foresight. First we have the so-called visions, often described as desired or target futures. Then we find scenarios ranging from multiple possible futures to a single success scenario that could, but not necessarily, be used as a vision. In some Foresight activity we can find forecasts, which are predictions or ‘informed guesses’ about the most probable futures. Some studies produce lists of key and emerging technologies where further research and investments may be needed. However, some of the most common immediate outputs of FHS include: lists of technological, economic, environmental, political and ethical (TEEPSE) drivers, trends and megatrends; as well as lists of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) and grand challenges (problematic issues of sufficient scale and scope to capture the public and political imagination). More recently, we see a growing interest in the production and analysis of lists of wild cards (uncertain future events with low ‘perceived probability’ and high impact) and weak signals (current issues/developments which are highly uncertain and ambiguous). More systematic and action-oriented studies tend to generate pathways (future directions) and roadmaps (details plans with one or more ways to achieve desired/target futures). Finally, we find models (using judgemental or statistical knowledge) and frameworks (including conceptual, methodological and analytical ones) as typical outputs of evidence-based Foresight. The main elements of the anticipating futures phase are used in the mapping of FHS outcomes.

The fourth phase of the FHS processes is about recommending futures. Many types of recommendations can be mapped against practices, players and “formal outputs” of a particular FHS activity. This will allow EFP to codify and measure the extent to which Foresight conducted at different levels (sub-national, national, European and international) suggest some types of recommendations. However, the STI orientation of FHS players quite often (but not always) makes the recommendations more relevant for actors in the research and innovation system. Even where recommendations are not explicitly stated in “formal outputs” of FHS (e.g. reports), often they can be detected implicitly. However, for the purposes of the EFP Mapping, it is important to be clear as to what is meant by ‘recommendations’ otherwise confusion could result. A couple of points should be highlighted:Thus, in the new EFP Mapping the twelve types of recommendations used in the Global Foresight Outlook report (Popper et al, 2007) are integrated into six broader categories:

- Recommendations are not the same as ‘Priorities’. The latter refers to topics and areas that have been identified as important in Foresight. By contrast, recommendations refer to actions that should be taken to address priorities. Care should therefore be taken not to confuse the two of them;

- Recommendations are wide-ranging in terms of what they cover and who they target. Policy recommendations are normally directed at the likes of ministries and other funding agencies, but recommendations from foresight panels and task forces often tend to be broader in scope and refer to a wider group of targets, including companies and researchers. Mapping efforts have had to be focused upon a broader set of recommendations than those that simply refer to public policies.

- - Policies and actions

- - Initiatives and actors

- - Appropriation and dissemination

- - (FHS) Research

- - Alliances and synergies

- - Investments and training

Finally, the fifth phase of FHS processes is about transforming futures. This refers to the ability to shape a range of possible futures (also known as futuribles) through six major types of transformations representing the ultimate outcomes or impacts of FHS activities:

- - Transforming capacities and skills

- - Transforming priorities and strategies

- - Transforming paradigms and current visions

- - Transforming socio-economic and STI systems

- - Transforming behaviour, attitudes and lifestyles

- - Transforming knowledge-based products and services

iKNOW has been featured in the media and several research projects:

DIE ZEIT (Germany), Financial Times (Germany), El Heraldo (Colombia), Prospective Foresight Network (France), Nationalencyklopedin (Sweden), EFP - European Foresight Platform (EC), EULAKS - European Union & Latin America Knowledge Society (EC), CfWI - Centre for Workforce Intellience (UK), INFU - Innovation Futures (EC), Towards A Future Internet (EC), dstl - Defence S&T Laboratory (UK), EFSA - European Food Safety Agency (EU), Malaysia Foresight Programme (Malaysia), Bulletins Electroniques more...